Part 1: Background and Intro to MPC

Intro to MPC Series

This is a first part of a series on teaching the fundamental of model predictive control for robotics. My goal for this series is to first and foremost provide interested graduate students and aspiring undergrads with a bit of introductory Knowledge of model-based control for robotics. The use of planning with models is not only important for getting robots to do the things we want, but it also teaches about the fundamentals of control theory, optimization, and the hidden assumptions that are often made in the field of robotics. So providing a series of blog post (or internet lectures or w/e you want to call it) is not only beneficial for new students interesting in learning robotics, but also beneficial as a refresher for myself and any researcher who wants to do research with me (I anticipate some posts will be about some of my research).

This first part of the MPC series (I know, not a very good name) is a bit of background knowledge of some fundamentals that you might want to be familiar with. This includes terminology that you might see in papers or lectures here and there and some of the assumptions that are being made in predictive control techniques (and in optimal control overall). I will then go into direct optimal control and how that relates to dynamic programming (in particular, we will derive a very common kind of mpc controller using dynamic programming). Then I will introduce the various versions of solving optimal control problems in the context of MPC. If you like my posts please continue sharing it with others and if you find any mistakes or think I should explain things differently then feel free to write me an email!

Some Background Knowledge about how to mathematically treat Robots

So the first thing you might want to know is how to define the robot, the state of the robot (its position, velocity, etc.), and the assumptions that we make about the robot. This includes how states are dependent on one another as well as how the robot is controlled.

The state of the robot is typically given as $s_t$ where $s_t \in \mathbb{R}^n$. This tells us that the way we describe the robot can be given to us as a vector of size $n$ on the real number line. The subscript $t$ tells us that the value of the state is taken at a specific time $t$ on some clock with a specific frequency (we are going to assume that the time frequency is $1$ and that $t$ takes on integer values for simplicity). You can also write this in a continuous time formulation $s(t)$, but we won’t get into that because you have to start dealing integration methods and continuous trajectories (which could be a topic in a later post -remind me-).

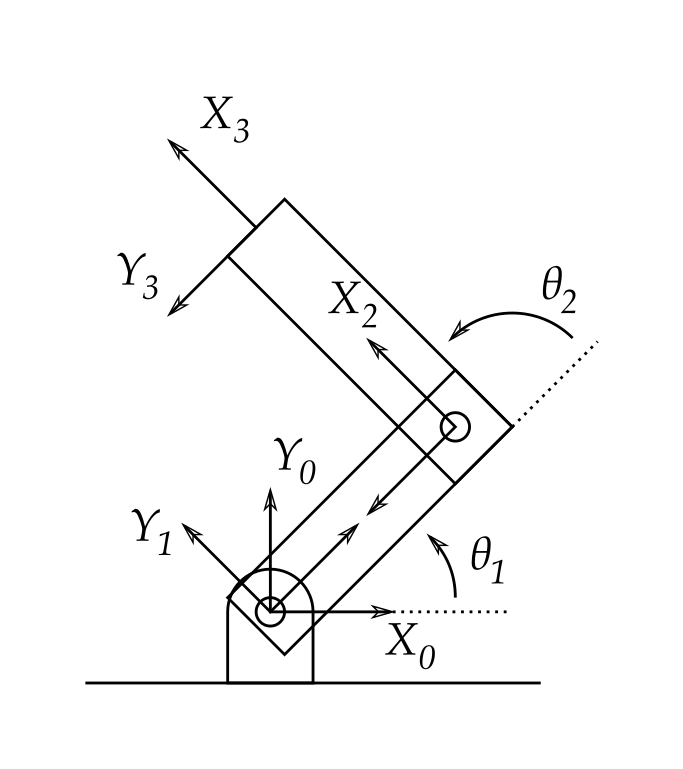

The state typically contain things that describe the configuration the robot is in time. Take a $N$ joint robot arm:

your state can include the joint position $\theta_t \in \mathbb{R}^N$ and the joint velocity $\dot{\theta}_t \in \mathbb{R}^N$ making the state equal to

\[s_t = \begin{bmatrix} \theta \\ \dot{\theta} \end{bmatrix}_t \in \mathbb{R}^{2N}\]The rule of thumb is to include what you can measure on the robot as part of the state (conditions are a bit more complicated than that, but we can worry about it later). You also want to include the set of states which you allows you to predict the next state in time and is only dependent on the current state and the physics of the robot. What this means in math is you want the following expression

\[s_{t+1} = f(s_t)\]where the term $f(s) : \mathbb{R}^n \to \mathbb{R}^n$ takes the state at the current time and tells you what the measurement of the state is at the next time step. This is also known as the Markov assumption, where the next state only depends on the current state. The function that the evolves the state, $f(s)$, can be thought of as the dynamics of the robot which you can derive from first principles using the Euler-Lagrange equations or Newton’s equations of motion (you can even get away with a kinematic set of equations if you assume that dynamics don’t matter). Either way your state should be something that you can predict into the future and measure because the goal of MPC is to get the current measurement of the state and predict what the state will be if you apply a set of control sequences. Sometimes you won’t have full access to the state in MPC/optimal control problem and this is called a partially observable state (another topic of a future post). For now, we will assume we have access to the full state of the robot.

You might be thinking, ok cool, how do we control the state and get the robot to do things? Well, great question! A+, you get a gold star. The way a control signal (or action) enters the robot will depend on the robot itself, but mathematically is defined in the same way. The control (or action) is commonly written as $a_t \in \mathbb{R}^m$ which is vector of real numbers of size $m$. For simplicity we will assume the the value of the controls can span the real number line, but there are control problems where the control is constrained to a bounded space (we won’t look at the now). Then the most general form to include the controls into the robot is to derive the dynamics $f$ with the control:

\[s_{t+1} = f(s_t, a_t)\]where now $f(s,a) : \mathbb{R}^{n\times m} \to \mathbb{R}^n$ which tells us that the next state depends on the current state and the action that was chosen (this becomes a special case of a Markov decision process when you include the set of actions). If we were to add noise to this process we would have to consider a distribution of possible states that the robot can be in due to noise. We will address noisy processes in a later post as developing controllers for such systems requires a bit more leg work. Some assumptions that are typically required for $f$ is that it is continuous (does not make the state jump around sharply) and it is differentiable (we can take the derivative of $f$ with respect to the state and control).

Defining a robot task

What we are going to want to do now is have a way to measure how well the robot is doing at a task that we want the robot to do. The way we can do this is by creating an objective function $\ell (s, a) : \mathbb{R}^{n\times m} \to \mathbb{R}$ which takes in the state of the robot and the action and returns a value which indicates how good or bad the robot is doing (good implies reward function, bad implies cost function). As with the dynamics of the robot, we want this objective function to be continuous and differentiable.

Starting at a measured state $s_0$ and given set of $T$ actions $a_{0:T-1} = ${ $a_0, \ldots, a_{T-1}$ } we can measure how well the robot can perform the task by applying the action at the state and evolving the state through time using the dynamics $f(s, a)$. Mathematically, we can write this objective as

\[\mathcal{J}(a_{0:T-1}, s_0) = \sum_{t=0}^{T-1} \ell(s_t, a_t) \\ \text{ subject to } s_{t+1} = f(s_t, a_t)\]where $\mathcal{J}$ is commonly known as the objective function. Now, if you chose $\ell$ to be a reward function (measuring how well the robot does) in order to get the robot to do the task, you will want to maximize this objective subject to the sequence of controls $a$. The inverse is true if $\ell$ is a cost function (measuring how bad the robot is doing).

Receding horizon

For MPC, we solve this optimization at every time step and apply the first action $a_0$ to the robot and recycle the $a_{1:T-1}$ actions for the next optimization iteration (initializing the last control using some heuristic). This step can be written down as

\[a_{0:T-2} = a_{1:T-1} \\ a_{T-1} = a_\text{def}\]where $a_\text{def}$ is a default initialization for an action. The state of the robot is measured and set to $s_0$ where the dynamics model is used to predict the value $\mathcal{J}$ from the action sequence $a_{0:T-1}$. We call this a receding horizon problem because the actions in the prediction horizon, $T$, is moving as time flows (see the image at the top of this post for an example description with slightly different notation). This is essentially the idea behind the receding horizon MPC approach. Solve the optimization problem every time a robot state measurement is received and replan the set of actions. This approach is has been shown to be pretty robust to model inaccuracies and sensor noise since replanning is updated based on the new measurement data. Solving the same problem without moving the horizon and remeasuring the state of the robot is the same as trajectory optimization

We still need to discuss what should be included in the objective function and the role of dynamics. In the following post, I will go over the special case where the dynamics of the robot are linear and we have a quadratic objective function.